Today, for the first time, during a

bike tour we were able to enter Bogotá's

Cementerio Alemán, the

German Cemetery.

|

| Cemetery administrator Gonzalo. |

The

German Cemetery is located on the south side of Calle 16, just west of Parque Renacimiento (once the Children's Cemetery) and two blocks west of the

Central Cemetery and the

British Cemetery.

Gonzalo, who administers the German Cemetery, told us that it opened in 1912 and is still active. It contains about 500 tombs and has capacity for another 500.

|

| 'Rest in Peace' |

Asian and European immigrants did not flood into Colombia as they did into more southern South American nations with more temperate climates. But immigrants, including German ones, have contributed a lot to Colombia's history and economy.

German immigrants played important roles in exploration, aviation, jewelry, manufacturing and business, amongst other areas, administrator Gonzalo said. In fact, Colombia's first airline - and one of the first in the world - was the Colombian-German Air Transport Society, founded in 1919. The company eventually evolved into

Avianca, today Colombia's largest airline.

|

| Leon de Greiff, poet |

Germans also were prominent in Colombian science, the most famous of them being

Alexander Von Humboldt, who traveled up the Magdalena River in 1800. Another was anthropologist

Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, who fled Hitler's fascism and did pioneering research on Colombia's indigenous peoples and founded the Department of Anthropology of the

University of the Andes, the first such department in Colombia.

|

Antonio Navarro Wolff, ex-guerrilla, and now a

top official of Bogotá. |

Other prominent Colombians of at least partially German descent include

Leon de Greiff, a Colombian modernist poet of the early 1900s, as well as his son

Boris, a chess champion, who died just two months ago.

Antonio Navarro Wolff, a leader of the M-19 guerrillas is now governor of Nariño Department.

German immigrants have also played important roles in the fabrics, coffee and banking businesses.

Colombia's most famous German immigrant is probably

Leo Siegfried Kopp, a German Jew who founded the Bavaria Beer Company and has become a popular saint in Bogotá's Central Cemetery.

But

Carlos Lehder, an associate of Pablo Escobar in the Medellin Cartel, was also of German descent.

|

Asking for a favor

at the tomb of

Leo Kopp in the

Central Cemetery. |

Colombia was also affected by the dark side of German history - fascism and the Holocaust. Colombia backed the Allies

during the Second World War, when some German nationals lost their properties and were either deported or sequestered in a hotel in the tropics. A small number of

Jews fleeing Naziism settled in Colombia, and a few Nazi war criminals came here. But their numbers were tiny compared to those who emigrated to nations like Argentina, Chile and Brazil.

|

This headstone carries a cross,

but the name sounds Jewish. |

Returning to the cemetery, like the British Cemetery, the German Cemetery is a peaceful, green oasis in the heart of the city. Not all those buried there are from Germany, or even of German descent. We saw headstones with Polish surnames and at least one apparently Jewish-German name. (On the other hand, the Central Cemetery contains many German surnames.) Perhaps those buried in the German cemetery are Protestants, since the tombs' style is much more plain and austere. Or, maybe those buried there simply felt more affinity for their German heritage.

Related posts:

A Glimpse of Historical Tragedy , Shoah Remembrence in Bogotá, Colombia in World War II , Karl Buchholz, Bookseller, Did a Great Colombia Hide a Nazi Past?, The Sinking of the Resolute

See also:

Germans in Latin America (Spanish).

Enrique Biermann, a professor at Bogotá's National University, has written a book about Germans in Colombia:

Distant and Distinct: German Immigrants in Colombia.

|

| An angel on a tomb. |

|

| Friede (Peace); The entrance to Bogotá's German Cemetery. |

|

| The pair of hammers mean the man was a geologist. |

|

| A coat of arms on a headstone. |

By Mike Ceaser, of

Bogotá Bike Tours

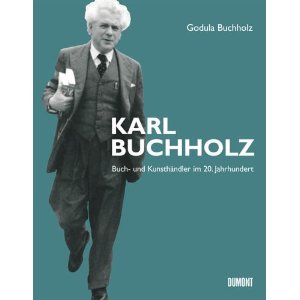

While reading about German immigration to Colombia, I discovered the remarkable story of Karl Buchholz, a German bookstore owner who became a minor legend in Bogotá.

While reading about German immigration to Colombia, I discovered the remarkable story of Karl Buchholz, a German bookstore owner who became a minor legend in Bogotá.